Frozen #1 (review)

(Joe’s Books, July 2016)

Writer: Georgia Ball

Disney Enterprises Inc (“Disney”), a multinational entertainment company based in the United States, have apparently licensed the rights to produce a comic book based upon its commercially successful animated motion picture, entitled “Frozen” (2014).

There is nothing remarkable about the two stories contained in this first issue. Both stories post-date the events of the motion picture. “Frozen” is a story of two princesses living in a fictional Arctic kingdom called Arendelle. The two are orphaned sisters, and one has dramatic ice-creating magical powers. Their friends include an almost sentient reindeer, a reindeer herdsman, and an animated snowman. No other aspect of the motion picture is required to understand the comic book.

The first story in this issue underscores the importance of compromise and communication in what is essentially a livestock land access dispute. Reindeer herdsmen wish to use a meadow as a thoroughfare for their migrating herds, as their usual mountain pass is snowbound. The meadow however is used by oxen, and the oxen’s herdsmen are deeply unhappy about herds of reindeer destroying the meadow grass upon which the oxen feed. The two sides confront each other. The queen and the princess comically interfere with the confrontational efforts of both sides. Queen Elsa then sweet-talks the parties to talk to each other about compensation involving dairy products and ox hair rugs. Then using her ice powers Queen Elsa builds a frozen bridge over the meadow for the reindeer to use, thus resolving the crux of the problem. If only all commercial conflicts involving destruction of property by roaming animals could be resolved by magic bridges, but to be fair, the target demographic, a pre-teen readership, would be expecting a dramatic use of ice powers and that was the opportunity for it.

The second story is entirely mundane even for pre-teens. The lead characters find a secret tunnel from the castle to a grocery shop and speculate on its historical use. And there the entirely pointless adventure ends.

Disney was never going to allow these characters and this title to do anything ground-breaking or controversial – Queen Elsa was not for hypothetical example going to introduce amusingly demagogic elections and a wacky democracy, and then upon conclusion of the transition graceful advocate (the princesses must remain within the commercially exploitable pantheon of Disney Princesses).

Fortunately, others have seen fit to add silly adult humour. Parodies abound (regarding the movie rather than this comic). Here are some examples:

a. a “Frozen” mash-up with video game “Mass Effect“:

b. the cast of “Frozen” in a parody of pop musician Michael Jackson’s music video, “Thriller“:

c. another video game mash-up, involving “Frozen” and controversial video game “Grand Theft Auto”, with the tag-line, “Do You Want To Do Some Blow, Man?” rather than the popular song from the motion picture, “Do You Want To Build A Snowman?”

Each of these is arguably an infringement of Disney’s intellectual property rights (see Disney’s policy on that here). History suggests that the tolerance Disney is exhibiting regarding the YouTube parodies, the PhotoShopped images, and the songs might not apply to a parody comic book of “Frozen”.

Disney has in the past been very aggressive about parodies. The story of “The Air Pirates” is the stuff of counterculture legend. The judgment of the court has the following legal case citation: Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates, 581 F.2d 751 (9th Cir. 1978). The broader saga of the litigation involving “The Air Pirates” and the rebellious and very silly behaviour of its creators is well-detailed here.

By way of example as to what the creators of “The Air Pirates” did to upset Disney, we set out below some of the less offensive covers and images:

But to be very fair to Disney, the creators of “The Air Pirates” went about as far out of their way as possible to be provocative, including sending copies of their comics to the homes of Disney’s board of directors.

Perhaps the fundamental differences between the scenario of “The Air Pirates” and the many parodies are that:

a. by reason of the Internet, the parodies are unstoppable. Back in the day of “The Air Pirates”, there was no ease of creation and replication. Nowadays, Disney can do little stop the systemic misuse of its properties because of the sheer volume;

b. by reason of the Internet, Disney has bigger problems. Bit torrent counterfeits eat in Disney’s profits. Disney’s resources are better-deployed towards activities which affect its revenue, as opposed to silliness on the Internet.

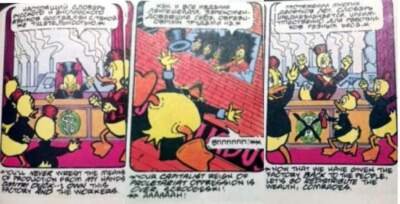

Perhaps also after “The Air Pirates” debacle Disney does not want to know. In the tenth issue of Howard Chaykin’s “Amerikan Flagg!” (1989, First Comics), Donald Duck and friends are depicted hurling Scrooge McDuck to his death in a Soviet putsch:

These three panels are buried within the issue, forgotten by all except devoted fans of Mr Chaykin’s body of work. Perhaps instead of you are quiet enough about it, and do not send copies of your parody to Disney’s directors’ homes, Disney will leave you alone.