Cage #1

Marvel Comics, October 5, 2016

Writer: Genndy Tartakovsky

“Cage #1” is a new mini-series from American comic book publisher Marvel Comics, featuring the African-American hero named Luke Cage. This is a character that is currently experiencing broad, renewed brand interest due to the launch of a live action Netflix television series (which, at time of writing, is enjoying positive reviews from both fans and critics.) Luke Cage’s defining trait is that he is an ex-convict who volunteered for a government experiment in exchange for freedom, with the experiment resulting in extremely durable “titanium” skin and enhanced strength.

The comic, on the other hand, does not feature the contemporary version of the character with his quiet but looming presence. Rather, it features the 1970s version of the character that went by the name “Power Man.” This version of the character sports a blue and yellow silk costume with a plunging neckline, large popped-up collar, a chain belt, and a metal head accessory that fans mockingly refer to as a “tiara.” The character’s costume was deemed silly and ridiculous even during the 1970s. It has long been a source of derision amongst fans, and also within the fictional superhero community.

Like his choice of costume, the 1970s version of Luke Cage also had an exaggerated jive slang vocabulary. During this period, “blaxpoitation” motion pictures were popular – movies dealing with black characters in tough and violent urban settings. It has been well-established that many fans – including African-American writer Christopher Priest – believe Luke Cage’s style of speech to be a misinformed white man’s idea of how an African American talks. This criticism is strangely directed even to Christopher Priest, that none of his black characters “sounded black”.

In any event, “Cage” #1 pares down Cage’s colorful jive talk. The character still uses slang and mouths off his trade mark catchphrases, but does not project as obtuse nor offensive.

The story in “Cage” #1 is representative of what fans would expect from author Genndy Tartakovsky. Mr Tartakovsky is a Russian-American animator, producer, and director whose influential body of work includes the popular television cartoons, “Dexter’s Laboratory”, “Samurai Jack”, and “Star Wars: Clone Wars”. Mr Tartakovsky’s works are known for incorporating mature themes into young adult narratives, which are then lavished with sharp wit and great comedic timing. These works have managed to stand the test of time, and are accessible to all ages.

In this sense, “Cage” #1’s plot is straightforward – all of the heroes in Harlem have disappeared, save for Luke Cage, who considers himself a hero but is in reality a paid mercenary. Cage is alerted to these events after interrogating the only person left in a police station, a convict who tries to bargain information for freedom. This amusingly backfires. Cage uses his superhuman strength to bend the jail’s steel bars during interrogation to remove the convict from his cell, and then squeezes the man back into the cell – sans clothes – after acquiring the information. Being nude in a prison cell leads to laconic conclusions.

On his way to find more information, Cage comes across the mutant superhero group X-Men, who are looking for missing team member Jean Grey (a character missing for entirely unrelated reasons), and a coterie of Luke Cage’s rogues gallery. These are B-level villains with silly gimmicks. One of these villains is Mr. Fish, who doesn’t have any powers besides looking like a fishman.

The villains’ ambush is motivated by the disappearance of the other super heroes. These bad guys decide to use their numbers to overwhelm Cage. Cage puts up a fight at first but decides to run away after realizing that the odds are against his favor. The issue ends with a cliffhanger as Cage is knocked out by a powerful punch from a mysterious assailant.

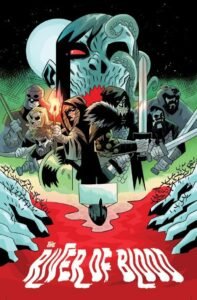

The World Comic Book Review makes it a point to avoid discussing art when reviewing a comic book, but in the case of “Cage,” a brief discussion about the art style is unavoidable. The comic’s author is so famous for his very recognizable art style, that part of “Cage #1”’s appeal most likely hinges on this artistic style being recognized by readers.

Mr Tartakovsky and frequent collaborator Craig McKraken are known for cartoons characterized by minimalist, angular visual designs accentuated by thick flowing outlines. It is an art style that is controversially mimicked by some newer cartoons to varying degrees. Many of these attempts fail, unsuccessful in capturing Tartakovsky and McKraken’s efficient and iconic use of screen space and colors.

“Cage” #1 uses a similar art style, and in a way, it helps set the tone of the comic. The cartoon-like visuals imply to the reader that the story is not to be taken seriously. And by reading the first issue alone, it is clear that its relevance to Marvel Comics’ well-groomed continuity is both unclear and inconsequential. People looking for a story with depth would best stay away. Readers looking instead for a fitting tribute to Luke Cage’s embarrassing 1970s comic book appearances may find this comic worth a read.