The Resurrected #1

Carnouche Productions, 2017

Writer:Christian Carnouche

This is a science fiction story, with modern political undertones. In particular, The Resurrected touches upon many contemporary issues in indigenous Australian relations. These heated topics, historical in origin but echoing into present-day Australian society, include Aboriginal deaths in custody, 19th century genocide of Aborigines by European colonists, and, importantly, the Stolen Generation. That term refers to the forcible capture and integration by the Australian Federal Government of very young Aboriginal children into white Australian culture. Cain Duluth, the story’s protagonist, appears to be a member of the Stolen Generation (although the timeline is wrong: the Stolen Generation occurred from the 1930s to the 1970s. That would place Duluth in his 70s, but here, he is a muscular and agile man clearly no older than his forties).

This story starts out with a juxtaposition between the horrid treatment of Aboriginal Australians arising European settlement in (what is now the city of) Sydney in 1788, through to Aboriginal deaths in custody in 1995, and then jumps ahead to a future set in 2032 and 2037. Duluth is a policeman working with a special United Nations agency in 2032.

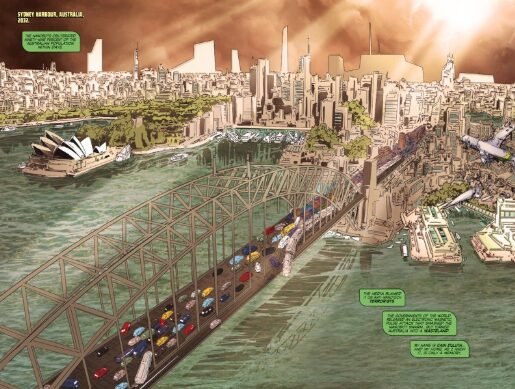

As he drives from a Nova Lucis, an artificial island which houses the United Nations and which is located off the coast of New York City, Duluth witnesses by way of a video call to Australia the apparent deaths of his wife Steph (a scientist at a multinational called Drexler Nanotech) and daughter Yindi. Duluth’s family and the entire continent of Australia are the victims of a terrorist nanobot attack, which is countered by an enormous electromagnetic pulse. Australia is in ruins. Page 7 of the story depicts a train hanging off the edge of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the wreckage of a commercial aircraft in Darling Harbour, and sunken ferries in Circular Quay.

Survivors are held at a place called Steward Island, where human rights activists struggle to have them released from detention (ironically echoing another issue in contemporary Australian politics, the imprisonment of undocumented seaborne refugees, from places like Syria and Iraq, in offshore detention centres).

Five years later, Duluth is struggling with the memories of his family’s deaths. Duluth’s detective partner is apparently Japanese, named Akimi Ozaki. Their police work is related to the deaths of the resurrected (or “rezzies”). These are apparently people who have used Drexler high technology to come back from the dead. Duluth is contemptuous of them:

Duluth: “And these fucking rezzies…”

Akimi: “You can’t blame people for wanting a second chance. Wouldn’t you take it?”

Duluth: “Second chance at what, Aki? This world? No thanks. Once you kick the bucket, you should stay dead. Why do these bastards get another shot? What makes them special?”

Death is a painful memory, and beneath the ridicule, Duluth is jealous and angry at those who, unlike his family, can return to life.

The dialogue of Duluth is a little too Australian. Plenty of Australians use the insult “wanker”, but “drongo” seems very quaint to our ears. The misuse of Australian dialects and colloquialisms in comic books is a topic we have previously discussed. It is odd that the writer, Christian Carnouche, who is Australian, would write dialogue with such heavy-handed idioms. Perhaps he has formed the view that a foreign audience would only perceive the protagonist as an Australian by reason of such forced language.

But:

1. the plot is strong. The religious protests against Drexler Nanotech, which in its quest to cure the world of disease brings back the dead, is believable in the context of the abortion debate. Drexler Nanotech is reminiscent of Google, a company which in its prospectus expressly disclaimed doing evil, but which proceeds in its business in ways which cause public uncertainty about its exercise of secret power. The pervasiveness of technology – not just the overt tracker bullets and floating motorcycles, but the advanced technology such as Google Glass-esque contact lenses, a thing called an “interchip” which translates foreign languages, and “neuro-stimulants” – is very apparent to contemporary readers, who on a day-to-day basis encounter similar new technological developments.

2. the characterisation of Duluth is well-thought through. The unfolding of the destruction of Sydney and Duluth’s consequential alcohol and sleeping tablet abuse is entirely consistent with the detective’s barely masked depression and anger. In the circumstances of the irreversible deaths of his family, it is no coincidence that Duluth works with the resurrected who have again died. The psychology involved in creating Duluth’ strained personality is impressive: does Duluth take secret delight in bearing witness to those who cannot rise again?

Mr Carnouche otherwise presents the reader with a question common to post-millenarian science fiction: when is a utopia actually a dystopia? There appears to be no pollution in this future Earth, and certainly no disease. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse have been reduced to two – death and war – by the progress of science. But,

a. do lenses which provide instant information on a deceased person improve the policing of crime, or do they reduce human memory? In contrast, Duluth identifies a suspect from recollection and hard work, in contrast with the trap of passively looking and being told by software and a database what the observer is looking at;

b. does knowing how to understand and speak French, by way of a device which translates the language, diminish the effort of learning the language? Duluth does not recognise the words, but he knows the angry tone of his boss, a Frenchman; and

c. does a mask for pain provided by a brain stimulant prevent a victim from working through his grief? Given his unrelenting pain, perhaps Duluth would benefit from better chemical intervention than alcohol and pills.

These questions all sit beneath the surface of this story, lurking like the monsters under the bed which we do not wish to confront.

Duluth clearly avoids the sorts of technology that killed his family. But in a dream, Duluth seems to remember an episode of being shot in the chest, and then being rebuilt in some way by his wife. The suggestion is that Duluth might not be what he seems, and that the apparently altruistic Drexler organisation is somehow involved in both that and the nanobot attack on Australia.

This is a book to follow, and to consider carefully for the questions it raises about where as a global society we are heading. The Resurrected is available on Kickstarter (with issue 2 due for publication in February 2018) or on the website.