Writer: Jonathan Hickman

Artist: Pepe Larraz

Graphic Designer: Tom Muller

Marvel Comics, August 2019-September 2019

Most of the Internet comic book community appears to be calling these titles HoX/PoX, because the two comic book series are meant to be read intertwined. We adopt the same nomenclature. HoX/PoX is a limited series published by American comic book giant Marvel Comics, about one of the most recognisable team of superheroes, the X-Men.

The “X” in the one of these titles, Powers of X, is to be read as the Roman numeral “ten”, thus rendering the title as “Powers of Ten”. Three of the story lines contained within HoX/PoX are based at various points in the past and future, each indicated by indices – XO, X1, X10, and X100. When Mr Hickman examines the future of humanity in these titles and timelines, he looks at them each as a futurist, incorporating X-Men lore.

Mr Hickman is plainly an enthusiast of writer Chris Claremont’s impeccable chores in the X-Men titles, particularly in the early 1990s. Mr Hickman repeatedly delves into this history. Nimrod, the main villain in this story, is a lethal artificial intelligence from the future, housed in an almost indestructible robot body, which appeared in Uncanny X-Men #191 back in 1985, a creation of Mr Claremont. Nimrod as an antagonist was a little underused. Mr Hickman changes that.

In Rick Remender’s quite brilliant run on Marvel Comics’ title X-Force in 2010, Mr Remender had a time travelling character named Deathlok note that the statistical likelihood of Nimrod’s rise was next to nil. HoX/PoX demonstrates that Deathlok’s assessment was very wrong. Instead, Nimrod as a predatory artificial intelligence, is an inevitable outcome of civilisational evolution.

Groundhog Life

Mr Hickman has said in an interview for the website Comic Book Resources in May this year https://www.cbr.com/jonathan-hickman-house-of-x-powers-of-x-interview/ that HoX/PoX is not a time travel story. Given the X-Men titles have over the years reduced the future of the Earth to something with the consistency of spaghetti and meatballs, we appreciate the sentiment.

But that statement by Mr Hickman fudges the truth. Moira McTaggart, a long-standing and relatively minor supporting character within the X-Men comics, for decades was always portrayed as a human, without superpowers. But in HoX/PoX, it is revealed that upon death, Moira’s personality and memories are reborn within her own in vitro foetus. In these two titles, the X-Men do not travel backwards and forwards through time, but for all intents and purposes Moira does. Within each new set of ambitions that Moira sets for herself in each new existence, she spawns vast consequences upon standard humanity, mutants, and the world.

And she does so, according to some beautiful infographics contained in the comic, ten times, each (save for her first, quite ordinary life) following a different pathway to defeat. One of those lived, life number 6, is as yet revealed. (Our best guess is that this involves the satanic storyline Inferno, also by Mr Claremont in the 1980s. This is suggested in one piece of slightly zany text within the titles relating to a character called Mr Sinister, of whom we speak further, below).

Chart-making and code breaking

The deployment by Mr Hickman of infographics is a tactic of story-telling which he has brought with him from what is perhaps our favourite comic book of the past five years, The Black Monday Murders (Image Comics). We have previously reviewed volume 1 – see https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2016/12/11/the-black-money-murders-1-2-review/ The Black Monday Murders uses infographics to describe the hierarchies of a financial cabal who gain wealth through the blackest of magic. It is a very effective way of assisting a reader to follow a story.

And in its own way, it adds significant value to a story. Instead of taking seven or so minutes to read a typical 21-23 page monthly comic book, the reader is compelled to ponder the mass of data contained in the infographic (here, created by graphic designer Tom Muller) and determine its relevance to the story. The comic becomes ponderous. We confess that we have already read these issues five times over – so far – endeavouring to digest the dense packets of information scattered throughout the titles.

Coupled with that is another trick deployed in The Black Monday Murders: the use of constructed scripts. A constructed script is the proper term for an artificial alphabet. In The Black Monday Murders, the constructed script is an ancient language which the main character, a detective, is endeavouring to decipher. In HoX/PoX, the script is an artificial language developed to enable mutants to communicate with each other in a script which non-mutants cannot understand. Halfway through HoX/PoX, Mr Hickman provides a key to the constructed script. This revelation of a key causes the reader to use the key and go back through the previous issues.

That creative vector, again, adds value and reader engagement to the comic. It is a clever experience to provide to readers, to enable a reader to revisit each issue so as to harvest additional, unlocked material.

There is also a lot of text within the pages of the titles, especially the first bumper-sized issues. At one stage we wondered if we were looking at a 21st century version of a pulp comic – the text drives the story, rather than the art as the champion of the medium.

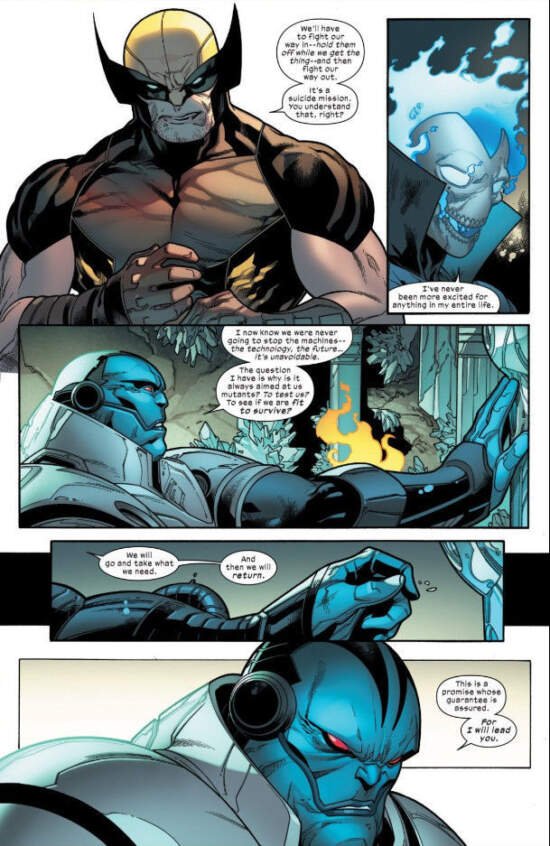

The story itself is not easy to follow – and, we think, deliberately so. We have ten re-births by Moira, each with key sections of plot development, in which Moira shares the learnings of her various existences with the players. That leads to very odd alliances. The most striking of these is the team comprised of the heroic brawler Wolverine and the X-Men’s arch-enemy Apocalypse.

These two, and other X-Men, coordinate a suicide mission in an effort to obtain critical information which could assist Moira in her next life.

Wolverine barely survives, but Apocalypse pays with his life, easily bested by Nimrod.

Evolution, but not for you

The story is intriguing in that it does not just look to the evolution of humans into militants. It also looks towards the evolution of civilisations. That evolution apparently includes the inevitability of machine intelligence. Nimrod is the apex of machine intelligence. Nimrod’s pedigree starts with mutant-hunting robots called Sentinels, a government program designed to capture or kill mutants, initiates by a man called Bolivar Trask.

Moira, during one of her lifetimes, becomes a soldier. In a series of panels reminiscent of the character Sarah Connor from the classic dystopian science fiction motion picture Terminator 2, Moira shoots every member of the Trask family in an effort to stop the rise of Nimrod. Yet even this does not stop the appearance of the Sentinels and the sentient Sentinel factories called Master Molds. Instead, they come into being in the “wild”. It seems Mr Hickman is telling us that artificial intelligence is an inevitable step in planetary – but not human – civilisational evolution.

The story draws upon the concepts contained in an irrational but compelling measure of civilisational development called the Kardashev scale. This scale of measures a civilisation’s level of advancement based upon energy requirements. The scale was devised by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Kardashev in 1964. Mr Kardashev proposed three levels:

- A Type I civilisation. This “planetary civilization” uses all of the energy available on its planet.

- A Type II civilisation, called a stellar civilization, uses energy at the scale of its star system. Civilisations using Dyson Spheres fall into this category.

- A Type III civilisation, called a galactic civilisation, uses the energy of its home galaxy.

We see that in the aspect of the story set in the future. In HoX/PoX, by the measure X100 (a thousand years from XO, the date of the epiphany of the telepathic mutant Professor Xavier to create a better world through the establishment of the X-Men), Nimrod and his peers have harnessed the Solar System. A giant Master Mold has made its way through past Jupiter, mining and absorbing two of the Jovian moons. This control of the resources of the solar system – a sufficient or prerequisite industrial base – attracts the attention of interstellar machine intelligences called the Phalanx (an alien machine foe of the X-Men), who decide whether or not the machine masters of the Earth will undergo “ascension”. What this means is not yet apparent. But whatever it is, it does not concern Homo Sapiens. The sole survivors of our species are kept under observation in a zoo.

In our review https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2019/09/17/scissorwalk-review/ of the comic ScissorWalk (a comic created by a curated AI), we clutched our pearls at the prospect of a machine intelligence with a sense of humour. Here is an extract from that critique:

A quote from an article in The Observer, however, gives us pause: https://observer.com/2019/07/teaching-artificial-intelligence-humor-robot-comedy/

“Artificial intelligence will never get jokes like humans do,” Kiki Hempelmann, a computational linguist from Texas A&M, told the LA Times. “In themselves, they have no need for humor. They miss completely context.”

“Teaching AI systems humor is dangerous because they may find it where it isn’t and they may use it where it’s inappropriate,” Hempelmann added. “Maybe bad AI will start killing people because it thinks it is funny.”

As anticipated by Ms Heppelmann, Nimrod as at X10 (one hundred years in the future) has a sense of humour, but it is not a pleasant one. Sarcasm and meaningless apologies litter Nimrod’s dialogue. And when Nimrod hammers Apocalypse, the machine mocks him. Survival of the fittest, Apocalypse’s Darwinian driver, is a cause of derisive contemplation for Nimrod. Nimrod happily demonstrates that Apocalypse is not fit, and will not survive.

But by X100, Nimrod is the size of a small drone and has a less antagonistic personality. Nimrod, sans threats, is no longer a tyrant but instead is a librarian. The contrast is sharp. Has Nimrod evolved from tiger to house cat, no longer troubled by any evolutionary pressure? It is a curious thought.

Brief Lives

This is a superhero comic, and so there is plenty of action. Apocalypse is routed by Nimrod, but we otherwise see:

1. a chimera called Rasputin fight Sentinels. This is a fascinating character for devotees of the X-Men. Rasputin’s power set includes those of Colossus (a Russian X-Man who can turn himself into a creature of lost indestructible organic steel), Magik (the sister of Colossus, who wields a demonic blade), Kitty Pryde (who can become intangible), and Quentin Quire (a powerful telepath). Rasputin and a non-combatant named Cardinal (a red-skinned version of the teleporting X-Man makes Nightcrawler) fight off a horde of Nimrod’s human and robotic shock troops. Rasputin’s friend Cylobel is captured by the Sentinels and put by a mocking Nimrod into a storage facility, to be slowly etched away for data.

900 years later, in X100, we see Cylobel’s corpse, floating, partially decomposed. Cylobel’s last words had been defiant, and in this chilling panel, ultimately proven false.

Rasputin is referred to as a “chimera.” As Scientific American explains https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/3-human-chimeras-that-already-exist/ to us, “A chimera is essentially a single organism that’s made up of cells from two or more “individuals”—that is, it contains two sets of DNA, with the code to make two separate organisms.” In Ancient Greek mythology, a chimera was a fire-breathing monster, part-lion, part-goat, and part-snake. Rasputin is described as the third-generation product of Mister Sinister, a longtime X-Men villain and malevolent geneticist. Mr Sinister so far has only a small role in this tale, although the text accompanying the story indicates that he will betray the X-Men to the Sentinels, nonetheless publicly executed by his new machine allies.

2. back in X1 (the present day), in Moira’s tenth life, an attack by the X-Men on a human Sentinel facility located near the Sun. Sentinels are nearby, mining Mercury for materials to make a robot called a Mother Mold, a prime factory for the construction of advanced Sentinels. The X-Men have intelligence that the Mother Mold will be the birthplace of Nimrod. They plan a surgical strike on the facility using a starship – the X-Men try to take out the Mother Mold, with terrifying losses.

There is a sensationally rendered scene by artist Pepe Larraz, of the Mother Mold falling into the Sun, disabled by Wolverine, who continues to hack at the machine even as it – and he – burns.

The Holy Land

We also see, in X1, the establishment of a new mutant nation, on the sentient island of Krakoa in the Pacific Ocean. The invitation to all mutants, good and evil, is reminiscent of the formation of the state of Israel after the horrors visited upon Jews in World War Two. Magneto, a character who survived the Holocaust, is almost “in tears” watching fellow mutants band together and celebrate what makes them stand apart from humanity.

And even the menacing Apocalypse is welcome (watched intently by a distrustful Wolverine), and undertakes to obey the laws of Krakoa. Apocalypse is “proud” of the rise of the mutant nation. It also helps that Apocalypse has a happy relationship with Krakoa, dating back to pre-history, such that Apocalypse is greeted with white doves upon his arrival on the island.

Cul-de-sacs

It is all very perplexing – are all mutants now X-Men? What does this all mean for the never-ending X-Men storyline? A quick scan of other comic book critique sites suggests widespread confusion amongst pundits, and we are no more enlighten than any other. Given the rapid fire pace of the release of these comics – one every two weeks (reminiscent, again, of Mr Claremont, in respect of his enormous fortnightly output in the ’90s) – we expect this critique will be obsolete as at the time we publish it.

But here is what we think, for what it is worth: In the very beginning of HoX/PoX, we see Moira approach a cheerful Professor Xavier on the day of XO. Xavier has no idea who Moira is. But Moira has known Xavier through lifetimes – including one where they were married. She invites him into his mind, where he can see her many lives. This suggests that each and all of these stories in HoX/PoX are realities which never came to pass.

In that regard, Mr Hickman can take great and meticulous delight in writing this extraordinarily captivating story, knowing that some of the concepts which would offend the X-Men’s long-standing readers – an effeminate Mr Sinister, Professor Xavier making peace with Apocalypse under golden sunbeams, the reincarnation of the dead through a combination of mutant powers, the X-Men team leader Storm sounding like a brainwashed mutant zealot – will never actually occur. Perhaps this liberty to create gives the story its breadth and inspiration.